Hole in the Wall: Buffalo, WY’s Outlaw Hideout

Beautiful. Secluded. Legendary.

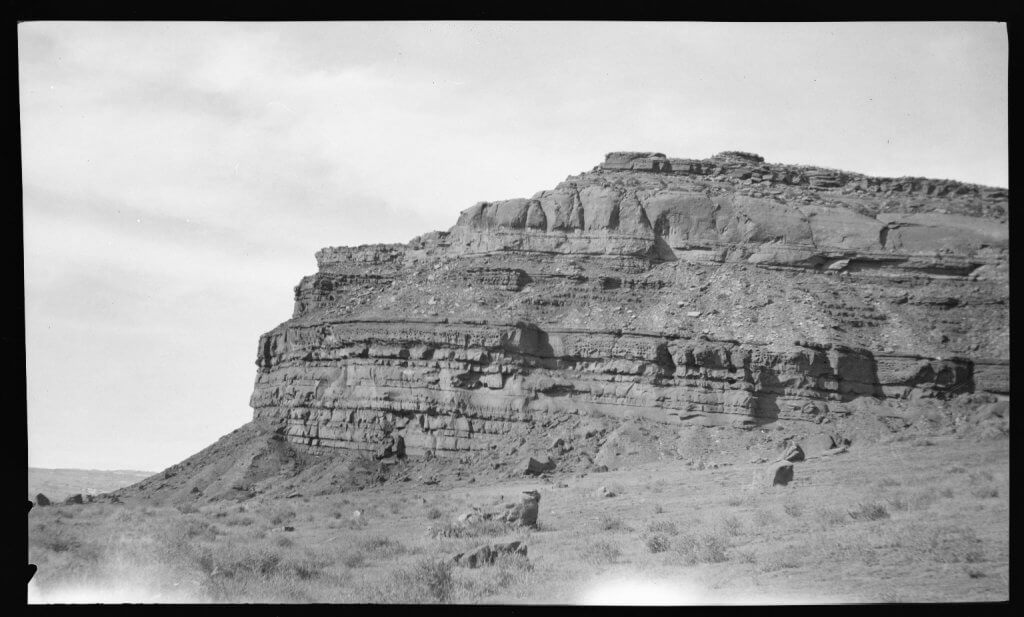

The cliffs and canyons in southwest Johnson County hold stories of Native American tribes, legendary outlaws, iconic lawmen, and a cattle war that shaped the West.

The Hole in the Wall is a special place – hard to reach but well worth the effort to enjoy some of the most beautiful scenery Wyoming has to offer.

Why Is It Called Hole in the Wall?

The Hole in the Wall was a hiding place for rustlers and outlaws who could use the imposing landscape to monitor visitors to the valley.

These days, visitors are welcome to explore the Hole in the Wall Trail or the Outlaw Canyon that surrounds the Middle Fork of the famed Powder River.

Also referred to as Red Wall Country, the Hole in the Wall name came into use in the late 19th century when cowboy Al Smith was asked where stage drivers should leave his mail. Smith told them to just leave it in the “Hole in the Wall,” and the name stuck.

This great region for hunting, fishing, hiking, and camping will leave you feeling like you’re in a special place cherished by the likes of Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, Harvey Logan, Flat Nose George Curry, and Nate Champion.

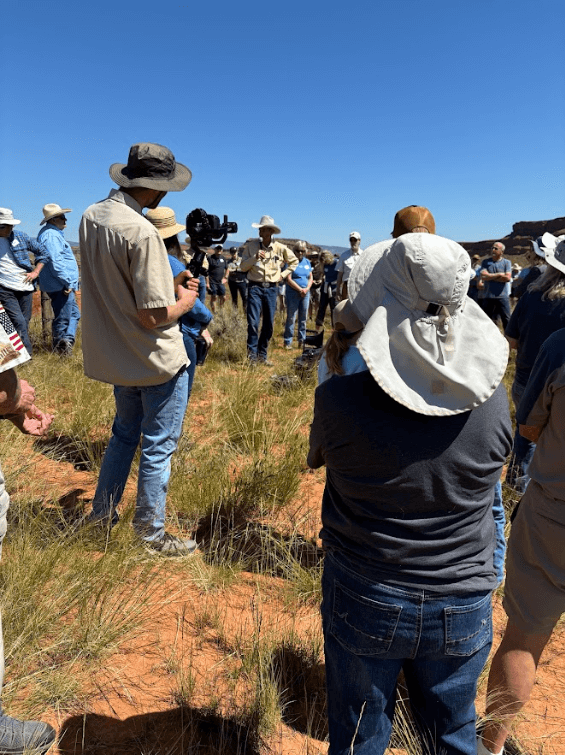

In 2023, the Johnson County Tourism Association began a project to showcase this area. The end result produced by Bighorn Films is a 70-minute documentary of the region’s history and its recreational opportunities. That full documentary is being considered for film festival premieres in 2026, but we are able to share with you shorter films featuring the area and the stories of the Hole in the Wall.

The History of Hole in the Wall

While signage is scarce in the Hole in the Wall, this is an important place in the history of the American West, from Native American presence to the Johnson County War to outlaws.

The Hoofprints of the Past Museum in Kaycee has exhibits about the Hole in the Wall and offers an annual historical tour each June.

The Crow People: Native American History

Evidence exists of Native American tribes in Red Wall country dating back for centuries. A mid-1970s archaeological survey of the area discovered 84 prehistoric sites along the Middle Fork of the Powder River and Beaver Creek with pictographs, weapons, pottery, and more.

The Lakota (Sioux) and the Cheyenne were in this region as far back as the 16th century. Rock cairn lines mark trails such as the “Sioux Trail” through the Hole in the Wall and over the Bighorn Mountains.

There is evidence of a buffalo jump, where Native Americans hunted bison by herding them over a cliff, that was used probably just one time – due to falling rocks – near the Middle Fork of the Powder River.

The Crow (Apsáalooké or Absaroka, translated as children of the large beaked bird), were in the region by the 18th century. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851 designated the region to the north and west of the South Fork of the Powder River as Crow territory. This included the Hole in the Wall valley.

The region had great meaning for the Crow. Some time the tribe split from the Hidatsa in the 16th century, a lengthy migration directed by tribal leader No Intestines brought them to Cloud Peak, the tallest of the Bighorn Mountains at 13,171 feet. The Crow considered this to be an important location in the universe.

Among the rock art in the Hole in the Wall are images telling the story of Lodge Boy and Spring Boy, a tale told by more than 20 North American tribes about two twins who avenged the death of their mother and brought her back to life. The story told through rock art in the Hole in the Wall may be from a combination of tribes, as the stenciled hands and arms predate the Lodge Boy figures, perhaps by several hundred years. It is possible that within the last 500 years, the Crow or Hidatsa enhanced an existing pictograph to create the pictorial version of the story.

This site and adjacent sites have 78 complete or partial stenciled hands and arms. The art in this area is unique because it illustrates all of the components of Spring Boy’s and Lodge Boy’s encounter with Long Arm.

The Dull Knife Fight of 1876

Exactly five months after the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, the Dull Knife Fight took place in Red Wall country, ending the Northern Cheyenne’s resistance in the Plains Indian Wars.

On November 25, 1876, two days after learning that Cheyenne tribes who had participated in the Battle at Little Bighorn had assembled a large village in the Bighorn Mountains, a U.S. Army force of 1,000 men under the command of Colonel Ranald Mackenzie came upon the camp of Dull Knife and Little Wolf on the Red Fork of the Powder River.

The U.S.-led forces, which included hundreds of scouts from multiple Indian tribes, attacked at dawn.

The Cheyenne village – said to be 200 lodges – was destroyed, and many Cheyenne fled into the cold of the mountains, leaving their clothing and blankets behind.

Six soldiers were killed, and three sons of Dull Knife died as well.

Many more Cheyenne were said to have frozen to death after fleeing the village.

Brigadier General George Crook wrote to the War Department in Washington: “This will be a terrible blow to the hostiles, as those Cheyennes were not only their bravest warriors but have been the head and front of most all the raids and deviltry committed in this country.”

Origins of the Johnson County War

North central Wyoming became a desirable place for cattle barons in the 1870s, using the open range to graze their large herds of livestock.

By the late 1880’s, for a variety of reasons, much of the former booming cattle industry was in the process of busting.

The cattle barons faced increasing competition as cowboys in their employ and increasing numbers of settlers to the region began building their own herds. The settlers began legally homesteading the choicest spots on the public range that the cattle barons were accustomed to having to themselves.

Tensions over the use of the range grew following a drought and then a disastrous winter of 1886-87. Great percentages of cattle herds were wiped out. The battle over land and unbranded wandering mavericks became violent, as the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, representing the interests of the cattle barons, sought to put an end to suspected rustling activity in lawless Johnson County.

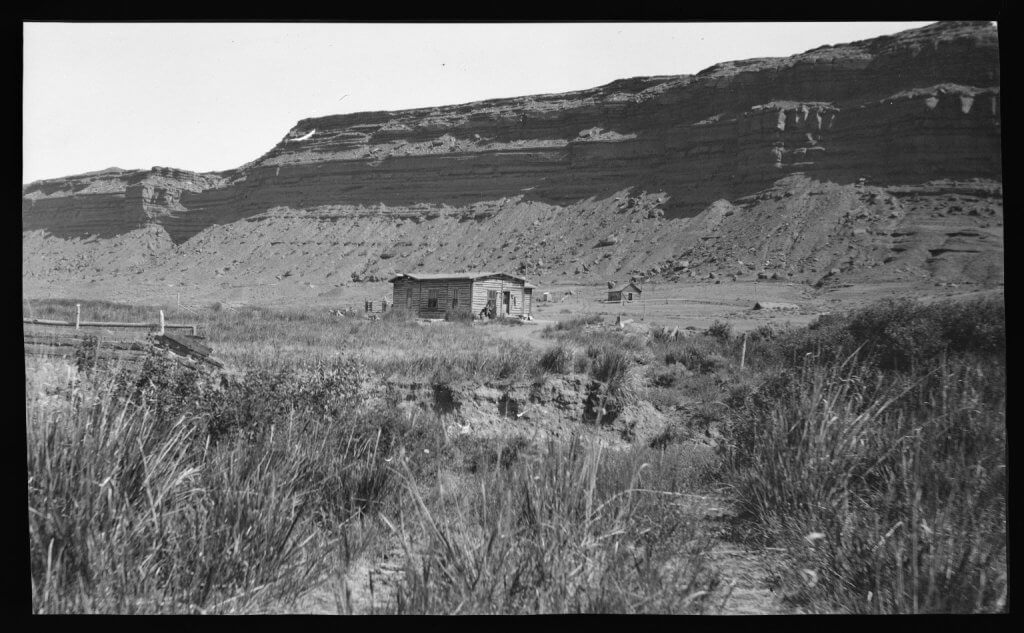

Nathan D. Champion, a Texan who worked as a cowboy and was well-known as a top cow hand at the EK Ranch in Red Wall country, was a natural leader of the so-called rustler element. He had acquired 200 head of his own cattle, and was elected president of a new stock association formed by the small ranchers to oppose the WSGA.

An attack on Champion took place in the fall of 1891 while he was staying at the Hall Cabin in the Hole in the Wall valley.

A group of armed gunmen approached the cabin, and several men entered with guns drawn. In the dim light of the cabin however, they missed Champion, allowing him time to grab his revolver and shoot back, wounding one and sending the others fleeing.

The attack led to a series of murders in Johnson County to eliminate witnesses. Ranger Jones was killed in November of 1891, and rancher John A. Tisdale was killed a few days later.

In April of 1892, the “war” was on with an invasion of hired gunmen and local ranchers working on behalf of the WSGA to eliminate the “rustler” element. They killed Champion and Nick Ray at the KC Ranch on April 9.

The invaders continued on toward Buffalo to eliminate many of the county’s elected leaders, including Sheriff Red Angus. However, they were forced to retreat to the TA Ranch, where locals surrounded and besieged them. The siege ended only after President Benjamin Harrison dispatched a unit from nearby Fort McKinney to stop the battle.

No one from the invading force was ever convicted, as a series of clever legal maneuvers by the Invaders’ attorney resulted in the county running out of funds to prosecute the case.

The conflict played a role in shaping land rights in the American West.

A Legendary Hideout: The Hole in the Wall Was Significant in the Outlaw Era

The Hole in the Wall was a place of refuge for outlaws after the Johnson County War in 1892. Locals who had been unfairly painted as rustlers and attacked by the cattle barons were understandably ambivalent about outlaws. This made it a great place for rustlers to reside and for others to escape the law. Outlaws such as Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, Harvey Logan (Kid Currie), and “Flat Nose” George Currie were known to frequent the area. Local outlaws included brothers Al and George Smith, among others.

Al Smith had a cow camp at the junction of Buffalo Creek and Spring Creek by which the stage road/mail route passed. When asked by the stage driver where he should put Smith’s mail, Al Smith replied “Just stick it in a hole in the wall,” referring to the white bluff running alongside the stage road near the cabin. The name stuck and eventually evolved not just to include the cabin location, but the entire valley.

The Hole in the Wall valley, flanked by a red wall on one side and mountains on the other, made it an easy area to contain livestock. Its remoteness, abundant water, grass, and friendly neighbors were ideal for outlaws retreating with stolen livestock.

Hole in the Wall Fight

The animosity between the new group of rustlers in Johnson County and large ranchers came to a head in 1897.

Bob Divine of the CY Cattle Company based in Casper was intent on ending the rustling taking place in the Hole in the Wall.

Perhaps he was more committed after receiving a note that said, “Don’t stick that damned old gray head of yours in this country again if you don’t want it shot off.”

In July of 1897, Divine and other CY Ranch cowboys joined with men from the Ogallala Land and Cattle Company, the Circle L Ranch, and U.S. Deputy Marshal Joe Lefors to investigate the Hole in the Wall. The force entered through a pass on the southern edge known as the Bar C gap. They rode past the ranch most commonly used by the Hole in the Wall Gang. After traipsing around three miles, they came upon three men – Bob Smith, Al Smith, and Bob Taylor, all known members of the Hole in the Wall Gang.

Divine and Smith already had a history, and tension was building between them. Divine asked if they had seen any of his cattle in the nearby area. Bob Smith is said to have replied “Not a Damn One.”

Believing that Divine was going for his gun, Bob Smith opened fire. This led to a shootout and chaos.

When the shooting had stopped and the smoke cleared, Bob Smith was lying dead on the ground with a bullet in his back.

Divine had survived but his horse had been shot and his son had been injured. Al Smith managed to escape suffering only a minor wound to his gun hand. Bob Taylor was captured and taken to the nearby Natrona County jail before being released.

The Hole in the Wall had not protected the outlaws and the spell was broken. Encouraged by his own success, Divine returned again at the head of a contingent of heavily armed men alongside two deputies to the Hole in the Wall Gang.

This raid was a success, and the posse managed to salvage several hundred cattle. Many of the Gang members watched while this happened, powerless to prevent it.

From the 1860s to approximately 1910, the pass was used by numerous gangs. However, it faded as the law was able to penetrate the territory effectively, learning its secrets.

Things to Do near Hole in the Wall

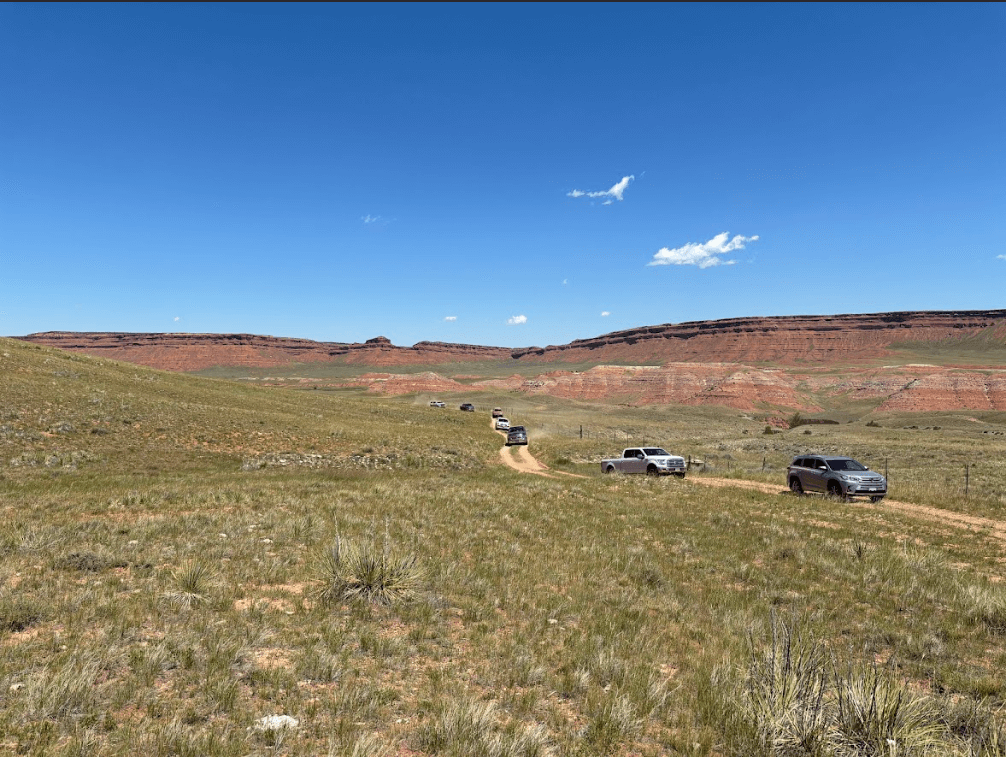

These days, the Hole in the Wall Pass and the Middle Fork Region surrounding it has around 80,000 acres (32,500 hectares) of public land, which is managed by the State of Wyoming, Wyoming Game and Fish, and the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management.

It is easily found and can be explored, located around 25 miles (56km) southwest of the Kaycee.

Please Practice Outdoor Ethics

Hole in the Wall Trail

The Hole in the Wall is a colorful and scenic red sandstone escarpment that is rich in legend of outlaw activity from the late 1800s, most notably Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch Gang. The “hole” is a gap in the Red Wall that, legend has it, was used secretly by outlaws to move horses and cattle from the area.

The area is primitive in nature, with no services. A 3-mile trail starts on state land and ends on BLM land at the Hole in the Wall.

The trail is on uneven, brushy terrain. Hikers are reminded that the trail is adjacent to private land, so hikers must stay on the trail.

Backcountry camping is allowed in the recreation area. Visitors should be skilled in cross-country travel and take adequate water, food, and fuel. Please pack trash from the area, and respect private property owners who are working with the BLM to make this an enjoyable recreation opportunity.

Outlaw Cave Campground

Outlaw Canyon, managed by the Bureau of Land Management, has a campground with 12 first-come, first-served sites.

Astride a blue-ribbon trout stream, this remote and picturesque campground features campsites with fire rings and one pit vault restroom. Use of the area is free with a 14-day limit on camping (as on all public lands).

The creek and Outlaw Cave is located at the bottom of a steep canyon, and it is recommended that only those accustomed to hiking should tackle the walk down and back. The hike is about a half mile from canyon rim to the river below, but it includes an elevation change of about 500 feet.

Outlaw Cave is just a small depression in the side of the canyon where several outlaws lived around the turn of the 20th century. A wood frame and cow hides were used to seal off the cave from the weather.

The area is primitive in nature. Visitors should be skilled in back country travel and take adequate water, food, and fuel. Please pack trash from the area, and respect private property owners who are working with the BLM to make this an enjoyable recreation opportunity.

Ed O. Taylor Recreation Area

This habitat area combines the flavor of the Old West with magnificent geological features and significant wildlife populations. The Ed O. Taylor Recreation Area is about 19 miles west of Kaycee near the south end of the Big Horn Mountains. The area straddles the Middle Fork of the Powder River. The 10,215-acre area was purchased in 1971 to ensure the protection of winter range for elk, which summer in the Bighorn National Forest. Protection of year-round habitat for mule deer also is ensured.

From April through October, pronghorn antelope may be observed on the open rangeland areas. The elevation gradient from east to west varies from 6,000 to 7,000 feet with steep canyon walls above the Middle Fork of the Powder River, Bachus and Blue creeks.

Sagebrush, mountain shrubs, and grasslands make up most of the habitat. Conifers, wet meadows, and rock outcroppings cover much of the remaining land. Two creeks and the Middle Fork of the Powder River provide water all year for wildlife and good fishing for the angler. You may find rainbow, brown, brook and cutthroat trout in these streams.

When you are not catching fish, watch for the many game species that live here. Blue grouse, sage grouse, Hungarian partridge, wild turkeys, doves and cottontail rabbits are plentiful.

Butch Cassidy’s Outlaw Cave is on the flanks of the Middle Fork of the Powder River Canyon. Steep canyon walls offered shelter and security for Cassidy and his men and have always provided protection for a variety of wildlife species. Swifts and swallows use canyon walls for nesting, while wintering deer and elk seek south-facing slopes for food and solar warmth. This remote winter range is not the place for the casual winter visitor. For those who make the effort during the warmer summer months, you will be rewarded by the spectacular scenery and recreational opportunities this area has to offer.

This area is closed to human presence from January 1 to May 14, and open beginning 8 a.m. May 15 through December 31.

Blue Creek Fishing Access

Blue Creek Public Access Area offers year-round access for fishing on Blue Creek with access limited to 50 feet above the high water line. Brook and brown trout can be caught in the stream.

Amenities include a graveled parking lot and a primitive outhouse. No camping is allowed.

To reach this location, take Exit 254 at Kaycee, travel west on Highway 191 (Mayoworth Road) for approximately eight-tenths of a mile, turn south on Highway 190 (Barnum Road) and travel for 16 miles to the end of the pavement. Turn south on to the Bar-C County Road and travel eight-tenths of a mile to the parking lot on your right.

How to Get to Hole in the Wall

By Car

Hole in the Wall

To access the area:

• Take Interstate 25 South from Kaycee to the TTT Road exit.

• At TTT Road exit, drive south about 15 miles to Willow Creek Road (County Road 111). This left turn is less than one mile south of the Johnson County-Natrona County line.

• Take this road west for about 5.9 miles until a right turn onto Natrona County Road 111A. There will be signage for Hole in the Wall at this turn up the hill.

Motorists will stay on County Road 111A and pass the Willow Creek Ranch entrance after 4 miles.

At 10 miles from the turn onto 111A,there will be a sharp right turn for County Road 105 with signage for the Hole in the Wall Access Route.

• As you travel along County Road 105 there are a number of livestock gates that must be opened and closed.

• Near the parking area there is a monument surrounded by fence marking the site of the Hole in the Wall Fight in 1897.

The access road terminates at the Hole in the Wall parking lot and trail head. A hiking trail to the “Hole” is about 2.5 miles on uneven, brushy terrain. Hikers are reminded that the trail, located on public land is adjacent to private land, so hikers must stay on the trail. Once at the Red Wall, hikers can also walk to the top of the Red Wall via the trail in the gap. It involves an elevation gain of about 300 feet over a short distance.

Outlaw Canyon

This scenic route offers views of the entire valley, including the Red Wall, on the way out to the canyon.

To access the area:

• Exit 254 for Kaycee.

• Head west on Highway 191 (Mayoworth Rd.) for about 1 mile.

• Turn left onto Highway 190 (Barnum Rd.) for about 17.5 miles.

• Stay to the left at the fork for Barnum Mountain Road and continue about 500 yards.

• Turn left onto Bar C Road. This road is an all-weather access road and travels directly through the headquarters of the Hole-in-the-Wall ranch.

• The road will continue south then turn west past the boundary to the Middle Fork Management area, and then another 5 miles to the campground. The trail begins at the campground.

Watch the Hole in the Wall Film to Learn More

Two years in the making, the Hole in the Wall is a documentary feature film that is as textured, majestic, and inspiring as the land it explores and celebrates. Rustic stories and the legends passed down by local families revive the heirloom spirit of our old American West.

Produced by Bighorn Films in cooperation with the Johnson County Tourism Association, this documentary takes you into the Hole in the Wall, where you will uncover evidence of Native American presence going back for centuries, learn about famous outlaws and the lawmen who chased them. And you will fall in love with a part of the country whose interesting history is equaled by its raw beauty.