Origins of Crazy Woman Canyon

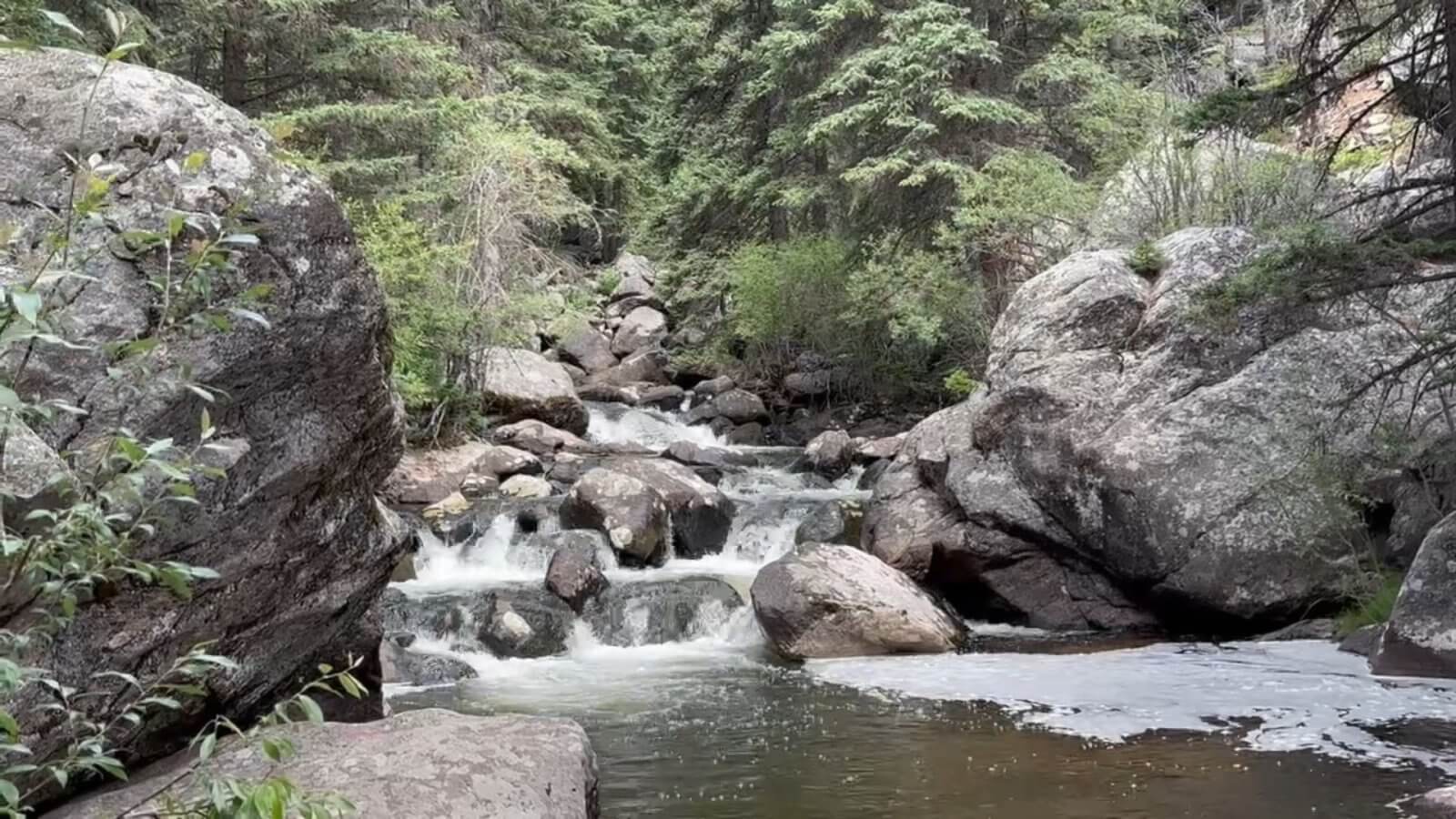

Crazy Woman Canyon is one of the hidden treasures of Johnson County, Wyoming, with high cliffs surrounding a fast-running creek that weaves its way over and around boulders like a miles-long cascading waterfall. The North Fork of the Crazy Woman Creek originates not far from the ridge of the Bighorn Mountains and tumbles down into the Powder River Valley. With a picturesque canyon – and many area businesses – using the Crazy Woman name, it leaves an impression. There are multiple stories for how the creek and canyon came to be named, one originating with the Crow tribe long before mountain men, trappers and prospectors passed through the area and created their own legends. The canyon was supposedly used as a strategic location in the Plains Indian Wars, a place to graze cattle, and a pass to reach the western side of the Bighorns.

How Crazy Woman Canyon Got Its Name

There are multiple legends that give rise to the name Crazy Woman Creek.

There are two local legends, a Crow legend, and the geographically questionable account of the Morgan family made famous in the movie Jeremiah Johnson. There is even a theory that says the name came from an error in communication for the Native American word for a prostitute, with the white men altering it to be foolish or crazy.

Most of the accounts are based on tragic events.

In one version, an Indian woman was the lone survivor after an attack on her village that left her tribe slaughtered. She went crazy and lived in a squalid wickiup. On moonlit nights, she was seen leaping from rock to rock in the creek. The Crow Indians felt that she brought good luck and left her alone, according to the legend.

The second tale told of a half-white, half-Indian trader who decided to call the fork of the creek his home. He built a cabin and filled it with goods. He eventually brought his white wife and more supplies.

He began gifting whiskey to the chief of the nearby Crow tribe, which made the chief act different from his usual quiet and dignified manner. This upset other members of the tribe, who confronted the trader. However, the trader supplied more of the whiskey, eventually asking for gifts in return. The trader ran out of his supply and said he had to get more, but the Crow feared he would take what they had given him and never return, or possibly trade with their enemy Sioux instead. They killed the trader in front of his wife and left her for dead.

But she lived, foraging the land for food and sometimes asking for help from Crow women.

A Crow warrior tried to bring her to the village, but she fled into the hills and was never seen again.

The story was allegedly relayed by Second Lieutenant George P. Belden, who served in the 2nd Cavalry and was stationed at Fort Phil Kearny in 1867 and 1868. He had previously lived with the Crow Indians.

The Crow’s mythological tale, chronicled by Edmund B. Tuttle in 1873 from Crow chief Iron Bull, is much less violent. It centers around the natural beauty and plentiful bounty of the Bighorn Mountains and Powder River, where the Crow had roamed more than 200 years before and where no Sioux would show himself. According to the story, the Crow had angered the Great Spirit, who made the rivers dry up and made the snow disappear from the mountains. The buffalo, elk, deer and other animals disappeared or died. The drought also brought death to members of the tribe.

The medicine man told of a vision where the Great Spirit asked him to gather the leaders of the tribe at the fork of the creek. Having eaten their ponies for survival, the chiefs walked on foot.

Arriving at the bluffs, they saw a bountiful supper spread on the bank of the stream and a white woman, who beckoned them. They had never seen a white woman before, according to the story. She told him that the Great Spirit would talk through her, and she said the wars displeased the Great Spirit. She said a peace must be made with the Sioux, after which Chief The Bear That Grabs must return to her.

Peace was made for the first time in a century. The woman told the chief to follow the mountain to the west, until he reached a river and a rock, where he was to shoot three arrows at it.

The Bear That Grabs began his journey. He looked back to see the woman rise into the air and float over the mountains until she disappeared over the highest peak.

He reached the rock and shot his three arrows. When the third rock was discharged, thunder shook the mountains and the earth trembled. A great fissure formed, and countless herds of buffalo came to fill the valley and hills.

The Crow were happy. They ate well and gave thanks to the Great Spirit and the white woman.

Iron Bull told Tuttle that when anything was to befall the tribe, the image of the white woman hovers over the peak at Crazy Woman’s Fork.

Prior to Crazy Woman Creek, the body of river was named Big Beard because of the type of grass that grew along its fringe.

The Historical Significance of Crazy Woman Canyon

Crazy Woman Canyon served as a pass into the Bighorns for Native Americans, as it climbs roughly 2,000 feet from the prairies toward the Powder River Pass.

The canyon also was said to be a staging area during skirmishes of the Plains Indian Wars from 1865 to 1876.

Cattle barons such as Moreton Frewen may have kept some of their prized cattle in the canyon for grazing later in the 19th century.

Some of the early settlers in the area of that time also used the canyon as a pass to the western side of the Bighorns.

As early as 1893, there had been a zig zag trail on Crazy Woman Hill for a sheep trail, stage route, and postal service.

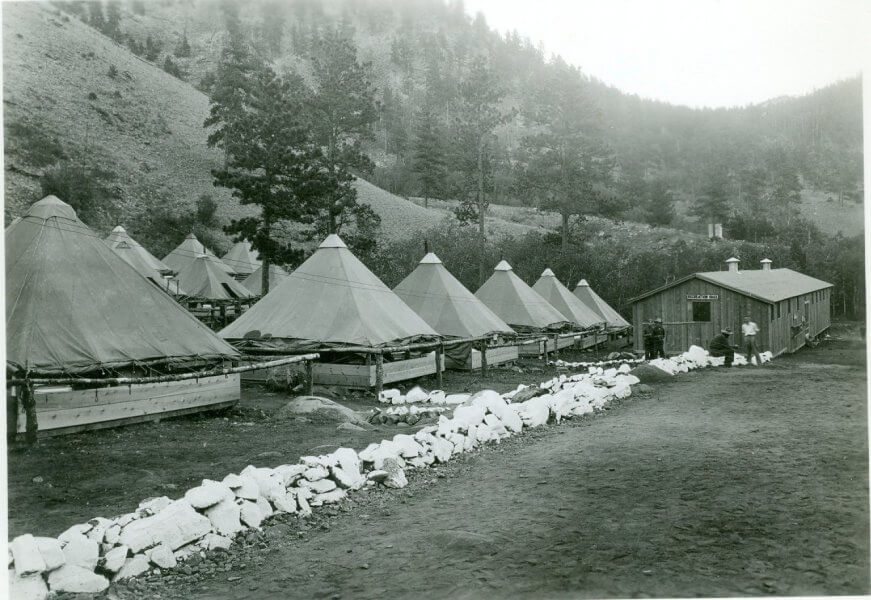

Finally, in the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps made a roadway through the canyon as part of the New Deal programs under Franklin Roosevelt. The Crazy Woman Canyon Truck Trail was to save 45 miles of travel for ranchers south of Buffalo going over to Ten Sleep.

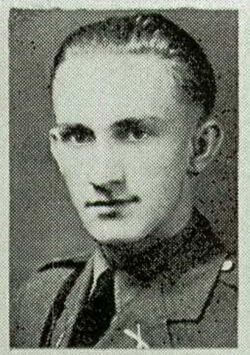

One of the members of the corps, Doyle Irvan Cross, died on July 1, 1934, from meningitis. He was 20 years old. A marker in the canyon serves as a memorial. Cross is buried in Highland Cemetery in Casper.

Exploring Crazy Woman Canyon Today

Crazy Woman Canyon today offers beautiful scenery and incredible camping experiences. It is one of the best scenic drives in the West, stretching about 13 miles from the mouth of the canyon into the mountains. There are several pullouts along the way to get out of the car and walk around, particularly in the area where the large boulders have fallen along the creek. Look for the portion on the east end of the canyon where the creek runs under ground. There also are natural grotto formations where the creek carved its way through the rock.

There is a hiking trail but it does not receive positive reviews do the overgrowth making the route hard to find or follow. Hiking into the hillside can be challenging due to the incline, but walking along the roadway is also an enjoyable hike.

Climbing in the canyon also is popular, with a few bolted routes on the canyon walls. (Check with The Sports Lure in Buffalo for information and gear.)

Heading west, dispersed camping areas allow for an overnight experience next to the creek in nature.

The creek offers a great opportunity to catch some trout for supper from June to September, provided that open fires are allowed.

Moose and other wildlife have been seen around the west end higher elevation of the canyon.

The scenic drive can take 1 ½ to 2 hours or more. The best approach is to take it slow due to the scenery, wildlife, and as a courtesy to others exploring the canyon.

Crazy Woman Canyon in Popular Culture

The Crazy Woman became known in popular culture through the movie Jeremiah Johnson, which was based loosely on the life of John “Liver-Eating” Johnston.

“Liver-Eating” Johnston was a 19th century mountain man who came by that name for his actions taking vengeance against the Crow Indians who in May of 1847 had killed his wife and unborn son. Johnson’s travels through the west included this part of Wyoming, as he claims to have ridden with Portuguee Phillips for some of the 236 miles between Fort Phil Kearny and Fort Laramie to carry news of the December 1866 Fetterman Massacre.

According to the story, it was an August day in the 1840s when Johnston came upon the Morgan family. Johnston and others say the events reported next took place in what is now Montana, but it may have been Wyoming.

Headed across the Great Plains from Nebraska, the Morgans – John, his wife Jane, three children, and their oxen – departed from a wagon train and struck out on their own. One night, John Morgan did not return from rounding up the oxen. Mrs. Morgan first sent her two sons and then her daughter to see what was the matter. Hearing the daughter’s screams, Mrs. Morgan grabbed an axe and headed to the horrible scene with a dozen Blackfoot Indians attacking her family. With her children dead or dying, the Indians moved toward Mrs. Morgan, who in her madness killed four of them. They departed, taking the wounded John Morgan but leaving his scalp.

This was the scene Johnston came upon as he was riding out from the Bighorns. He could get no sense from Mrs. Morgan. He helped her dig four graves for her three children and Mr. Morgan’s scalp.

He stayed nearby, cut some logs, and built Mrs. Morgan a small cabin over the course of three days.

In time, the Crazy Woman’s story became a well-known tale in the West. Mrs. Morgan stayed near the cabin and the graves, despite attempts to get her to relocate to a settlement. She reportedly hunted for sustenance. Johnston made pilgrimages, leaving her offerings and departing silently. He said the Crazy Woman took part in a “shrill keening for her dead, each night come sundown,” the time of day when her children were killed.

Overland parties and other mountain men also tried to leave items for her. Indians stayed far from her cabin, however.

It was rumored that Mr. Morgan escaped from the Blackfeet camp, although he never reacquainted with Mrs. Morgan. It was said he roamed the mountains in a demented state.

The Crazy Woman died in that winter of 1866-67, starved to death. She had gone blind from a blow at the hands of the Blackfeet in the 1840s and could no longer hunt for game.

The Crow Indians built a large cairn for her grave, out of respect for Johnston, her friend and their enemy who had killed so many Crow in his lifetime..

The 1972 movie Jeremiah Johnson, starring Robert Redford as the title character, was based on Liver-Eating Johnston’s life.

Plan Your Visit to Crazy Woman Canyon

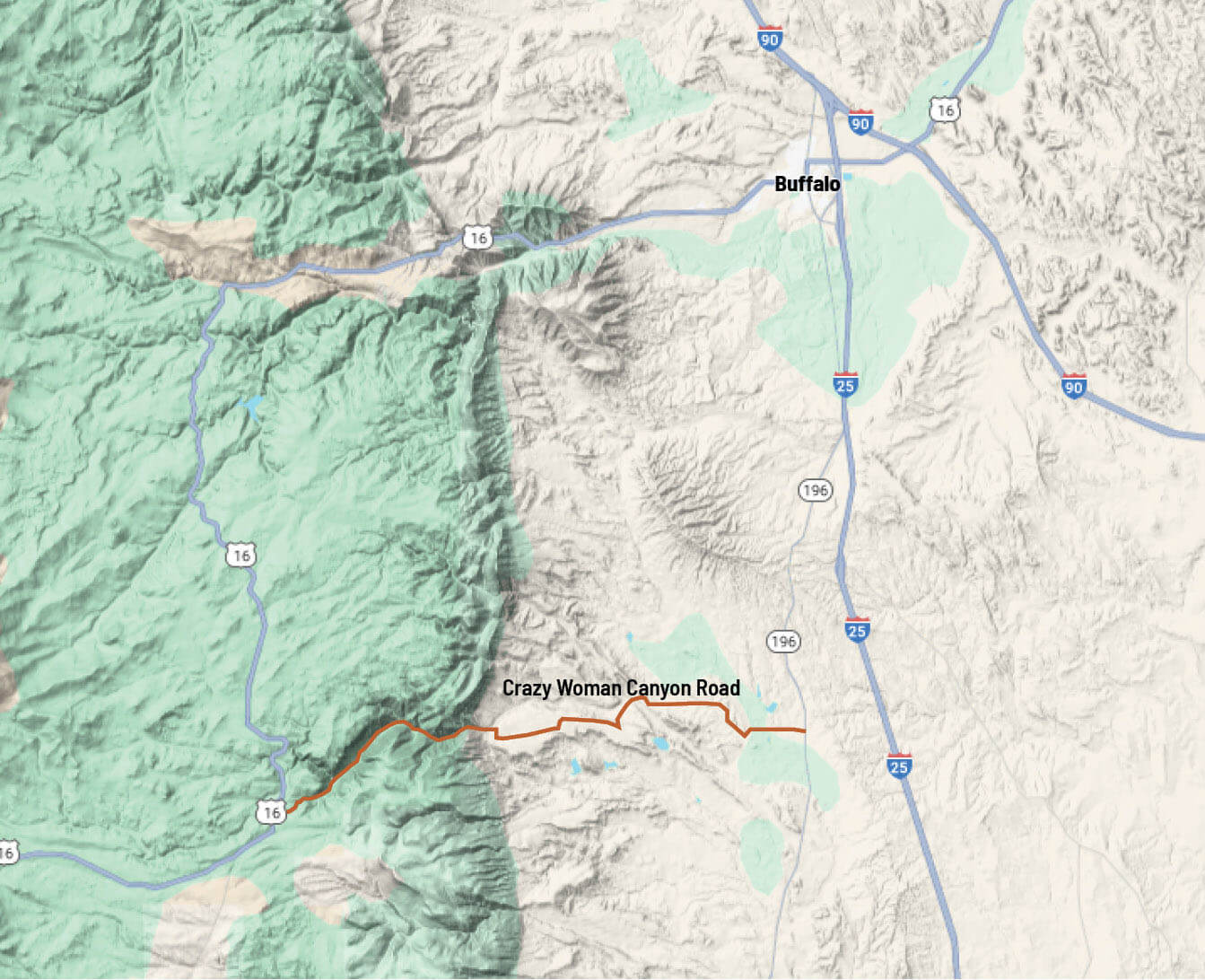

Crazy Woman Canyon can be explored from late spring through fall, when conditions are dry.

The road is narrow in spots but also has places for two-way traffic to pass. The road was graded in the last few years and is fine for compact cars, but four-wheel drive and high clearance are preferred. Motorhomes and heavier vehicles are discouraged. Vehicles traveling uphill have the right of way. A good rule of thumb for traveling the canyon is “check first and go slow.”

From Old Highway 87, about 11 miles south of Buffalo, look for signs to turn to Muddy Guard Reservoirs. A white concrete block building stands on the northwest side of the intersection. Road signs mark it as Crazy Woman Canyon Road and Johnson County Road 14.

On U.S. Highway 16 in the mountains, about 26 miles west of Buffalo, a large brown Forest Service sign marks the turn for Crazy Woman Canyon Road/FSR 33 and Muddy Guard.